The Windows at St. Thomas’

History

The stained glass windows in St. Thomas’ Church were inspired by those in St. Mark’s Chapel at Bishop’s University, Lennoxville, Quebec, Canada where Father Ralph Hayden, Rector of St. Thomas’ from 1919 to 1933, had gone to school. They were planned by him in collaboration with Mr. Alexander A. C. Higerty, New York Representative of the English firm Heaton, Butler and Bayne, Ltd., artists in stained glass. All the windows in the church were made in England by Heaton, Butler and Bayne. Those in the chapel, which was built later, are now thought to be by Earl E. Sanborn of Annisquam, Massachusetts. The architect of the church, E. Leander Higgins of Portland, seems not to have been involved in he choice of subjects or the execution and installation of the windows.

The stained glass windows in St. Thomas’ Church were inspired by those in St. Mark’s Chapel at Bishop’s University, Lennoxville, Quebec, Canada where Father Ralph Hayden, Rector of St. Thomas’ from 1919 to 1933, had gone to school. They were planned by him in collaboration with Mr. Alexander A. C. Higerty, New York Representative of the English firm Heaton, Butler and Bayne, Ltd., artists in stained glass. All the windows in the church were made in England by Heaton, Butler and Bayne. Those in the chapel, which was built later, are now thought to be by Earl E. Sanborn of Annisquam, Massachusetts. The architect of the church, E. Leander Higgins of Portland, seems not to have been involved in he choice of subjects or the execution and installation of the windows.

The subject of the great West window, which is actually at the east end of the church, is the Sermon on the Mount. Over the altar is the Te Deum Laudamus, depicting Christ in Majesty with three archangels. The windows along the two sides of the nave present an orderly progression of the important events in the life of Christ, and have been used as a teaching series in the church school program.

The four windows on the Gospel side of the nave present the important events before His crucifixion, which is graphically illustrated in sculpture on the Rood Beam. The three on the Epistle side illustrate the important occurrences after the crucifixion.

Each window is divided into three scenes enclosed in a slender framework with an ornamental canopy. The canopy serves two purposes. First, it disassociates one subject from another and second, it gives the necessary gothic effect. The deep and rich colors in the glass were purposely specified by Father Hayden as he desired to achieve an atmosphere of prayer about the church above all else.

The subject of the lower part of the West Window in the rear of the nave is the Sermon on the Mount. It portrays Christ teaching outside the city of Capernaum and is inscribed, “But Seek Ye First The Kingdom of God and His Righteousness and All These Things Shall Be Added Unto You.” This was the first window which Heaton, Butler and Bayne, Ltd. designed and created using The Sermon on the Mount as the subject. This window was dedicated and blessed on Sunday August 10, 1930. –

The subject of the lower part of the West Window in the rear of the nave is the Sermon on the Mount. It portrays Christ teaching outside the city of Capernaum and is inscribed, “But Seek Ye First The Kingdom of God and His Righteousness and All These Things Shall Be Added Unto You.” This was the first window which Heaton, Butler and Bayne, Ltd. designed and created using The Sermon on the Mount as the subject. This window was dedicated and blessed on Sunday August 10, 1930. –

All of the windows by Heaton, Butler, and Bayne are highly detailed, realistic scenes taking place in a three dimensional space beyond the window tracery. This approach is different from medieval stained glass, which tended shows simpler, more symbolic representations of the events in a flat and decorative manner similar to manuscript illuminations. The idea that an accurate picture of reality was important had become important in the Renaissance, but had gradually been supplanted by the theatrical displays of the Baroque. In the mid nineteenth century in England a group calling themselves the Preraphaelites had sought to restore both the precision and the piety of the early Renaissance, which they thought had become endangered in the modern mechanical world.

At the time these windows were designed, their high realism was losing place to a more authentic recreation of Gothic glass styles. The leading advocate of the gothic style, Ralph Adams Cram, whose book Church Building is known to have influenced the design of Saint Thomas, admired the craftsmanship of Heaton, Butler and Bayne but at the same time disliked the spatial perspective in the scenes. He felt that windows should again become translucent walls, not holes opening on landscapes. The chapel windows are examples of what Cram considered a better style.

The window is a superb example of the kind of picture window Cram didn’t like. The listeners spread across all five panels, as if behind a screen whose gray stonework extends the dark wood of the actual frame. The mountain town by the sea rises in the background. In center Christ speaks not just to the listeners, but directly to us.

Above the Sermon on the Mount are five smaller lights, which share the theme of a champion of truth confronting or combating the forces of evil. The center one just above the figure of Christ shows St. Michael casting out the Devil. On the left are two outstanding Old Testament figures at moments of confrontation: Elijah and the Priests of Baal, and Moses destroying the tablets. On the right side are two outstanding preachers of righteousness from the Christian era. They are St. Paul preaching to the pagan philosophers at Athens, and John Wyclif sending forth his poor preachers to condemn ecclesiastical abuses and to preach the Gospel in English throughout England in the 14th Century.

Above the Sermon on the Mount are five smaller lights, which share the theme of a champion of truth confronting or combating the forces of evil. The center one just above the figure of Christ shows St. Michael casting out the Devil. On the left are two outstanding Old Testament figures at moments of confrontation: Elijah and the Priests of Baal, and Moses destroying the tablets. On the right side are two outstanding preachers of righteousness from the Christian era. They are St. Paul preaching to the pagan philosophers at Athens, and John Wyclif sending forth his poor preachers to condemn ecclesiastical abuses and to preach the Gospel in English throughout England in the 14th Century.

The dress and features of several of the listeners in the lower windows correspond to the dress and features of actors in the scenes above in ways that were probably not a coincidence. Elijah, Moses, the Athenian philosophers, even (though less certainly) Wyclif have their counterparts in the lower windows. In this way the artists convey the timelessness of Christ’s teachings. Moses and the prophets are in the audience, as are St. Paul and Wyclif and those who, in turn, hear them preaching. This kind of detail occurs throughout the windows of the church and, when perceived, can add a new depth to the appreciation of the thought as well as the craft that went into their conception and execution.

The first of the story windows combines three events of the Nativity story. In the first panel the Angel of the Annunciation carries a scepter headed by a fleur-de-lis, which combines in one symbol the lily of the annunciation and the scepter of Christ’s kingship. The dove of the Spirit appears over Mary’s head. The prie-dieu and the tiled floor are architecturally in keeping with the style of the church.

The first of the story windows combines three events of the Nativity story. In the first panel the Angel of the Annunciation carries a scepter headed by a fleur-de-lis, which combines in one symbol the lily of the annunciation and the scepter of Christ’s kingship. The dove of the Spirit appears over Mary’s head. The prie-dieu and the tiled floor are architecturally in keeping with the style of the church.

In the central panel Joseph stands of Mary with the Child. Joseph’s robes and to an extent his features correspond very closely to those of Christ in Majesty in the Te Deum window over the altar, perhaps to indicate the extent to which Jesus was Joseph’s child.

In the Presentation window there is an interesting detail: a caged dove brought as an offering. Are we intended to think of the very similarly portrayed dove in the Annunciation window? And therefore to see the Presentation as foreshadowing the Passion?

The second window covers Jesus’ youth and the story of John The Baptist. Again, physical resemblances are used to make connections. John, who was Jesus’ first cousin and older by only six months, is shown as very similar to Jesus. His pose in the central window is almost identical to the of Jesus in the Transfiguration, and the presence at his feet of a lamb refers to his own imminent death as well as to his identifying Jesus as the Lamb of God.

The second window covers Jesus’ youth and the story of John The Baptist. Again, physical resemblances are used to make connections. John, who was Jesus’ first cousin and older by only six months, is shown as very similar to Jesus. His pose in the central window is almost identical to the of Jesus in the Transfiguration, and the presence at his feet of a lamb refers to his own imminent death as well as to his identifying Jesus as the Lamb of God.

In these three windows Jesus is shown moving from youth to his acceptance of his mission at his baptism.

Next is the triptych showing Christ’s ministry. In the center the Spirit identifies him as the Messiah, in the company of Moses and Elijah. Moses is shown with the two horns that he often has, which refer to a passage in the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, which described Moses as horned (cornutam) which had by the Renaissance lost its symbolic meaning of crowned with rays of light. Michaelangelo’s Moses has small actual horns in reference to this tradition. The window tries to have it both ways, with horns of light.

Next is the triptych showing Christ’s ministry. In the center the Spirit identifies him as the Messiah, in the company of Moses and Elijah. Moses is shown with the two horns that he often has, which refer to a passage in the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, which described Moses as horned (cornutam) which had by the Renaissance lost its symbolic meaning of crowned with rays of light. Michaelangelo’s Moses has small actual horns in reference to this tradition. The window tries to have it both ways, with horns of light.

The two side panels are designed as if the radiance from the Spirit in the center were moving through Jesus to the recipient of his grace. In both, his gesture completes the movement from the top of the center panel to the lame man on the left and the child on the right. In this way the three panels are brought together as a single representation of the single idea of Christ being the light of the world, and that light bringing healing and nurturing to those in need.

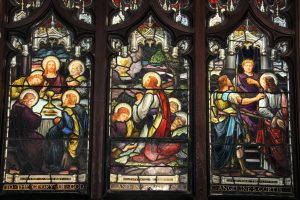

The last window on the Gospel side is the Passion narrative. This Is My Body shows the Last Supper, with John asleep on Christ’s shoulder. Thy Will Be Done shows Christ’s agony in the garden of Gethsemane, with all the disciples now asleep, and Behold the Man shows Christ being brought to Pilate. –

The last window on the Gospel side is the Passion narrative. This Is My Body shows the Last Supper, with John asleep on Christ’s shoulder. Thy Will Be Done shows Christ’s agony in the garden of Gethsemane, with all the disciples now asleep, and Behold the Man shows Christ being brought to Pilate. –

Behold the Man is actually misnamed, since that phrase is said by Pilate to the crowd after Jesus is scourged and crowned with thorns. The window shows the moment when Pilate, who is given the square jaw and short hair of a Roman emperor like Hadrian or Tiberius, asks Jesus to defend himself. His confusion and distaste for his position are clear in his face, and he seems on the point of making his dismissive reply, “What is truth?”

One architectural note is that, while all the frameworks of the windows are gothic, Pilate sits between two classical columns in front of a purple drapery. Those who believed that gothic was the only fitting style for a church here make their point by identifying classical architecture as the style of Pontius Pilate.

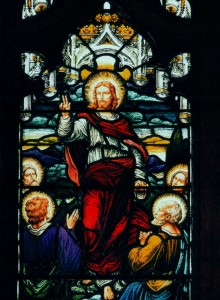

Over the altar is a window with four lancets. In one of the central lights is a portrayal of The Reigning Christ wearing the eternal crown and holding the scepter and orb. The next panel contains The Angel Offering Incense. The outside lights are occupied by the Archangels, St. Michael and St. Gabriel. The traceries above the main lights contain angels and the inscription reads: “To Thee All Angels Cry Aloud: The Heavens and All the Powers Therein.” Along the bottom of the window, just above the donors’ names is the text, “We Praise Thee, O God: We Acknowledge Thee To Be The Lord.” In its entirety the window represents the Te Deum Laudamus. –

Over the altar is a window with four lancets. In one of the central lights is a portrayal of The Reigning Christ wearing the eternal crown and holding the scepter and orb. The next panel contains The Angel Offering Incense. The outside lights are occupied by the Archangels, St. Michael and St. Gabriel. The traceries above the main lights contain angels and the inscription reads: “To Thee All Angels Cry Aloud: The Heavens and All the Powers Therein.” Along the bottom of the window, just above the donors’ names is the text, “We Praise Thee, O God: We Acknowledge Thee To Be The Lord.” In its entirety the window represents the Te Deum Laudamus. –

Originally the window was to complete the story told along the Gospel side with a Crucifixion. By the time the window was donated, the Rood Beam had already received the figures of the crucified Christ with Mary and John.

Heaton, Butler and Bayne’s man in New York, Alexander Higerty, wrote to Father Hayden about the difficulty of fitting a crucifixion in a window with four panels and thus without a central panel for the cross. He suggested that while the architect might have had good reasons for a four-light window, he hadn’t made the glass artist’s job any easier. Later the same day Higerty wrote again from his home suggesting the Te Deum theme, with the angel with a censer portrayed clearly deferring to Christ. By placing Christ in the left of the two central panels, with a radiance flowing from the space between the two center windows, Higerty has suggested the idea of Christ seated at the right hand of the Father, whom no man has seen at any time.

Thus the problem of the four windows led to a creative solution, and rather than stressing the crucifixion, the window appropriately completes the story with Christ reigning in majesty. –

First on the Epistle side are the events of the Resurrection. As the Gospel side tells of the event leading to the crucifixion, the Epistle tells of those flowing from it.

First on the Epistle side are the events of the Resurrection. As the Gospel side tells of the event leading to the crucifixion, the Epistle tells of those flowing from it.

The Resurrection window shows the sleeping guards in Roman uniforms. This is traditional, despite the fact the Matthew has Pilate refusing the use of his soldiers and telling the priests to station their own guards. While it is true that the Romans had custody of Christ from his delivery to Pilate until the crucifixion, their presence at the tomb is not scriptural.

The Noli Me Tangere window shows the moment in the garden when Christ tells Mary Magdalene not to embrace him. She clasps her hands together instead, as if she has to grasp something if not Christ. Christ reaches toward her, his right hand almost touching her halo, as if he too would like to have embraced her, but his new condition has placed a barrier which he knows should not be crossed. Mary is shown with her hair uncovered, and the long, beautifully drawn fall of hair recalls her identification in Western tradition with the weeping woman who washed Christ’s feet with her hair. There is a tradition that Mary became a penitent, and grew her hair long to form her only clothing. So by emphasizing her hair, the artist not only bring to mind these two extensions of the story but draws attention to the poignancy of physical beauty and its loss.

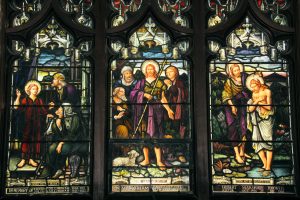

The Great Commission shows the scene from the end of Mark’s Gospel, in which Jesus appears to the disciples for the last time and sends them out into the world. Here, as in the companion Resurrection window and the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus is looking directly at us, challenging us as he challenges the disciples. These windows are not meant merely to describe, but to inspire.

The next window shows the operation of the Spirit. It is directly opposite the Transfiguration window on the Gospel side, and here again the central feature is the descending Dove. –

The next window shows the operation of the Spirit. It is directly opposite the Transfiguration window on the Gospel side, and here again the central feature is the descending Dove. –

This time the window shows Christ ascending into the radiance associated with the Spirit, then the Dove descending, crowing the disciples with tongues as of flame, and then, as the visible radiance that preceded the voice of Christ to Saul on the Road to Damascus.

All three windows stress the divinity of the risen Christ as the origin of the Church. Through the operation of the Spirit Christ continues to inspire and instruct his followers, and to convert his enemies into his advocates.

The last window is intended the bring the story, if not to the present, at least to our shores. –

The first panel shows the Baptism of Ethelbert, King of Kent, in 597 by St. Augustine of Canterbury. Though taken to refer to the arrival of Christianity in Britain, the event actually marks the reestablishing of the authority of the Roman church after the fall of Rome. Christianity had been well established in Britain under the Romans, with Saint Alban becoming the first English martyr under Diocletian’s persecution. The tradition persists that Joseph of Arimathea, who buried Christ is his own new tomb, founded a community at Glastonbury. And the Celtic church, which had grown from contacts with the Christians in Alexandria, was the leading keeper of Christian scriptures and traditions throughout the chaos of the fall. But Augustine, as the representative of Pope Gregory the Great, is here shown founding the church in, if not of, England.

The first panel shows the Baptism of Ethelbert, King of Kent, in 597 by St. Augustine of Canterbury. Though taken to refer to the arrival of Christianity in Britain, the event actually marks the reestablishing of the authority of the Roman church after the fall of Rome. Christianity had been well established in Britain under the Romans, with Saint Alban becoming the first English martyr under Diocletian’s persecution. The tradition persists that Joseph of Arimathea, who buried Christ is his own new tomb, founded a community at Glastonbury. And the Celtic church, which had grown from contacts with the Christians in Alexandria, was the leading keeper of Christian scriptures and traditions throughout the chaos of the fall. But Augustine, as the representative of Pope Gregory the Great, is here shown founding the church in, if not of, England.

The center panel similarly purports to show the First Prayer Book Service in America in Jamestown in 1607. This overlooks not only the Spanish who had been in America for a century (who of course didn’t use the Prayer Book), but George Weymouth, who held a service on an island off the St. George River in 1605. The Minister is the Rev. Robert Hunt, M.A. The other figures are Captain John Smith and Edward Maria-Wingfield. Two Indians peer over the stockade in the background, rather like the shepherds in the Nativity window across the aisle. There is a window similar to this in Old Christ Church, Philadelphia, also created by Heaton, Butler and Bayne. –

Consecration of Bishop Seabury as First Episcopal Bishop of the United States who was consecrated by the Scottish Bishops of Aberdeen, after English bishops had refused to recognize the legitimacy of the breakaway American church. This window is similar to one created by Heaton, Butler and Bayne for the American Memorial at Shakespeare’s church, Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-on-Avon, England. This and the previous window show slight departures from the style of the others, and perhaps they were copies by less experienced craftsmen.

And thus, on a memory of old controversies, the story of the church ends at the door, leading us back into the world, reminded of the great events of our faith.

The four windows in the chapel sanctuary are the Gospelers: St. Matthew, St. Mark, St. Luke, and St. John. The small window in the nave of the chapel is St. Mary Star of the Sea. It is signed along the bottom (using a diamond stylus) Earl E. Sanborn. While we have letters and bills for the Heaton, Butler and Bayne windows in the church, we have not found any correspondence about the chapels windows, but based on the stylistic differences and the difference in the time of their design and installation, we feel that all five of theses windows were probably done by the same artist, and that that artist was Earl Edward Sanborn. –

Sanborn was from New Hampshire. He studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, then worked with the Boston firm of Charles J. Connick before opening his own studio first in Boston and then in Annisquam. He designed windows for the chapel of Trinity College, Hartford, and some of the first windows in the choir of the Washington Cathedral. He dies in 1937, not long after the chapels windows were installed.

The four Gospelers are placed like statues against a gray background resembling a stone niche or a quilted tapestry. This is the style that Cram was advocating: not a picture window as he called it, but a translucent piece of the architectural fabric. In Sanborn’s career at the Washington cathedral in would be involved in a controversy about the amount of gray or silver in windows. The fashion was by the late 1930s moving away from muted grays towards the brilliant colors of windows such as the magnificent ones in the Spanish cathedral of Leon. –

All but St. John carry a book that refers to their Gospels; St John carries the cup with a serpent that was used as his symbol in reference to a tradition that there had been an attempt to poison him. Also, in contrast to the others, John is depicted as young, in reference to his status as the beloved disciple who fell asleep at the Last Supper.

The last window in the chapel is in a deep embrasure in the base of the bell tower wall. It depicts Mary on a stormy ocean between a ship and the lee shore towards which the storm is driving it. In the sky is a bright star. The image clearly depicts the medieval Latin hymn Ave Maris Stella (Hail, thou Star of Ocean.) –

The hymn goes back at least to a manuscript of the ninth century founded in the Irish-found Swiss monastery of St Gall. It has been wrongly to St. Bernard and also, without sufficient authority, to St. Venantius Fortunatus (d. 609), author of Pange Linguax and Hail Thee, Festival Day. Its frequent occurrence in the Divine Office made it most popular in the Middle Ages, many other hymns being founded upon it. The tune has been adapted as the Acadian National Anthem, and the association of Mary with the sea made the image an appropriate choice for Camden and for the chapel, whose carved reredos depicts Christ calming the sea. –

The presence in the chapel of a window dedicated solely to the Virgin suggests that Father Hayden might have had the idea of a Lady Chapel in mind, but did not want to be explicit about his intentions. –

And finally there is the angel with the trumpet, high up under the roof of the nave above the Sermon on the Mount. This little window is similar to those designed by the greatest of the preraphaelite painters Edward Burne-Jones, the close associate of William Morris and John Ruskin. A drawing even more closely resembling the Burne-Jones angel hangs in the Parish house.